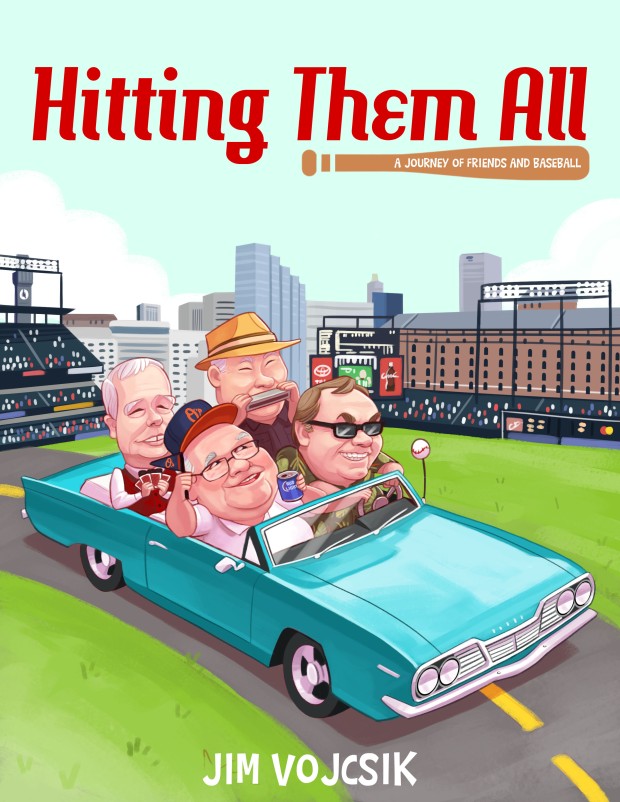

This is another excerpt from my new book, Hitting Them All.

“The Orioles proved that clean living and thinking plus Brooks Robinson at third base can bring victory with honor.” — New York Times, October 16, 1976

The Poker Group

“Seven Card Stud, Queens are wild and whatever follows,” Jake called out the cards as he dealt them around the table, “Four of diamonds, Jack of Hearts, King of Spades. There’s a Queen, followed by a three, so threes are wild, but that could change. And the dealer gets a seven of Hearts.”

Jake worked as a sales rep for a family business that sold construction and building supplies. He had a medium build and was ruggedly handsome with short grey hair turning gray at the temples. Jake appreciated a good joke, loved to tell stories and often made funny, random remarks. We called him “Diamond Jake”, a suitable nickname since he liked to gamble at the casinos in Atlantic City a couple of times a year. He played Caribbean-style poker against the dealer because it was the casino game with the best odds of winning. Jake bore a physical resemblance to Jimmy Carter’s son, Jack, so we also called him “Jack.” If this book were a movie, William H. Macy would be cast as Jake.

Six players sat around the table at my house in a small town on the Eastern Shore of Maryland — a regular group of guys that got together once a month to play small stakes poker. As we placed our bets, I studied the other players and thought about how I had met them. We rotated the game so everyone had a turn hosting it at their house. The most anyone won or lost was $20, unless you had the hot hand or really sucked at poker like Biggy.

We gave Biggy a cheat sheet that showed the progression of the winning hands from lowest to highest: a pair, two of a kind, two pair, three of a kind, etc. He would stare at the sheet and ask, “Does a straight beat a flush?” Biggy reacted to what was in front of him and didn’t think too far ahead. My wife called him the dumbest smart person she knew. Before the game started, we asked Biggy if he wanted to pay his $20 in advance so he could play all night without having to think about placing any bets. It was said in jest, but on most occasions, he would have come out ahead.

Gary Shore sat to the left of Jake. They became friends while pursuing an MBA degree together at a local university. Gary was a successful financial planner and investment manager. He took risks playing poker in the same calculated manner that he managed his clients’ portfolios. He rarely won or lost big, but usually came out ahead.

Gary was born and raised, went to college and lived his entire life in the state of Maryland. He became my first friend when I moved to the Eastern Shore after accepting a job as the director of a well-known non-profit organization. We shared a passion for baseball and bonded immediately over our love of the Baltimore Orioles and Brooks, Robinson, Gary’s favorite player.

Gary had short hair and wore thin, wire-rim glasses that gave him a scholarly appearance. Unlike most of the members of his profession, he was a Democrat and a keen student of history and political science. Physically, he was tall and broad in the shoulders and built like an offensive tackle, which was the position he played on his high school football team. Gary had a dry sense of humor that bordered on being sarcastic if you didn’t know him. He resembled a giant teddy bear, especially with his shirt off, so if this book was a movie, Will Ferrell would play Gary.

Gary introduced me to Bob Bigelow, a fellow Jaycee who sold insurance at a reputable firm. When I first came to town, Biggy invited me to lunch and we became friends. He was originally from Delaware and grew up as a Phillies’ fan, so we had that in common. Biggy’s nickname fit his appearance. He was tall and big-boned with broad shoulders and a wide chest. He had short brown hair and wore a thick brown mustache and wire-rim glasses. He was obsessed with his body, enjoyed working out in the gym and was in excellent physical shape. Biggy often seemed tense like a tightly-wound spring that could snap at any minute. If this book was a movie, the role of Biggy would be played by a young John Goodman.

Johnny Bender sat to the left of Biggy. I first met Johnny when we played against his softball team in a Jaycee District tournament. He stacked his team with “ringers,” amateur softball players who never saw a gavel drop at a Jaycee meeting, but we beat them anyway. Before the game started, Johnny boasted that his team was going to kick our ass and he wasn’t even playing. During the game, he argued with the umpires and taunted our fans from the coach’s box like a professional wrestling manager. After Gary invited Johnny to join the poker game, I got to know him better. He was a master plumber by trade, short and stocky with a full beard and thin, wire-rim glasses. Zach Galifianakis would be the perfect casting choice for Johnny, if this book was a movie.

My friend, Steve Stone, sat next to Johnny. We called Steve, “Sonny Boy Slim” or “Sonny” for short because he was a decent amateur musician who played the acoustic guitar and blues harps in several different keys. He knew the chords to several songs by heart, but didn’t always remember the words. Sonny’s namesake, Steve Stone, was a good starting pitcher for the Orioles in the 1980’s. For my 40th birthday, Sonny gave me a book about the Baltimore Orioles with the inscription, “Life begins at 40, but you’re still in the fourth inning.” Sonny was average height and weight, and he had an ageless quality about his appearance like an old blues man. Tom Hanks would be Sonny, if this book was a movie.

I sat next to Jake and observed the action at the table as it unfolded. “Last card, down and dirty, time for the final bet.” Gary and Sonny folded and Johnny bet a quarter, “I’d pay a quarter to watch a monkey fuck a doughnut,” he said in his raspy voice. With two Kings showing, Biggy called his bet. I didn’t know what he had, but I wasn’t worried. I had two wild cards and an Ace in the hole with another wild card on the table for a hand of four Aces. Jake interrupted my thoughts, “It’s a quarter to you, Mac.”

“I’ll raise it 50 cents. Let’s see who’s here to play poker,” I challenged. Jake had a boatload of hearts with the possibility of a straight flush that would beat my Aces, but he just called my bet. “What are you so proud of Mac?” Johnny asked as he bumped the bet another 50 cents. Biggy folded. Jake and I knew that Johnny liked to bluff, so we called his bet. “Read ’em and weep, four Jacks,” Johnny boasted as he turned over his cards. “Not so fast, I have four bullets,” I said and glanced at Jake. “Straight flush in hearts, boys,” he said and I grimaced. It was a nice pot for Jake, but there’s nothing worse than having the second-best hand in a poker game.

We took a bathroom break and refreshed our drinks. When everyone returned to the table, Jake told us he had accepted a temporary job assignment at his company’s Richmond, Virginia office. “Why don’t you boys come down for a visit and we could go to a minor league baseball game? The Atlanta Braves have a Triple A team in Richmond.” he said. “Better yet, we could drive down to Richmond for the weekend and catch an Orioles game in Baltimore Sunday on the way home,” Gary chimed in. “I’ll check the schedule when it comes out and get a date.” And that’s how the baseball trips got started.

The Best of Them All

Situated in downtown Baltimore a few blocks from the Inner Harbor, Oriole Park at Camden Yards was the first “retro” classic major league ballpark and the trend-setting design for several modern ballparks that followed. Although it has a seating capacity of 40,000, there is an intimacy about Oriole Park that makes it one of the best places to watch a game. There is a statue of Babe Ruth at the ballpark. The Babe’s roots were in Baltimore where he grew up and learned to play baseball. Legend has it that his father’s saloon once stood where home plate is now located.

Camden Yards has been the site of some notable games since it was built in 1992, including Cal Ripken Jr.’s record-setting 2131st consecutive game on September 6, 1995, but it has yet to host an Orioles’ World Series game. Over the years, we have seen several games at Oriole Park, which may have biased our opinion. But we have seen them all, and Oriole Park at Camden Yards is at the top of the list.

At the Game

It was a hot, sticky July day with the temperature over 100 degrees in the sun. We sat in the left-field bleachers in the section where Chris Hoiles’ home run landed in the fourth inning. Fernando Valenzuela, the former L.A. Dodger, pitched a gem of a game for the Orioles, allowing only two hits in eight innings in a 6-0 win over the White Sox. Cal Ripken, Jr. got his 2000th career hit, and later, drove in a run with a double. Hoiles’ home run was his 18th of the season, tops among American League catchers. Three future members of the Hall of Fame played in the game: Ripken, Frank Thomas, “The Big Hurt,” and Tim “Rock” Raines for the White Sox.

,