This is an excerpt from my new book, Hitting Them All — A Journey of Friends and Baseball.

At the corner of historic 18th St. and Vine in Kansas City next to the American Jazz Museum is a baseball museum dedicated to preserving the history of Negro League professional baseball in America. The museum was a fascinating tour and the price of admission included entrance to the American Jazz Museum next door. At one time, 18th and Vine was a hotbed for great Jazz performers, including Count Basie and his orchestra, Charlie Parker, Lester Young and Big Joe Turner.

Moses Fleetwood Walker was the first black professional baseball player in the United States in 1872 before black players were banned from the sport. Professional baseball was an all-white sport from 1900 until after World War II. Ken Burns, the noted filmmaker, in his excellent documentary film about baseball referred to the United States during this period as a “Shadow Society.”

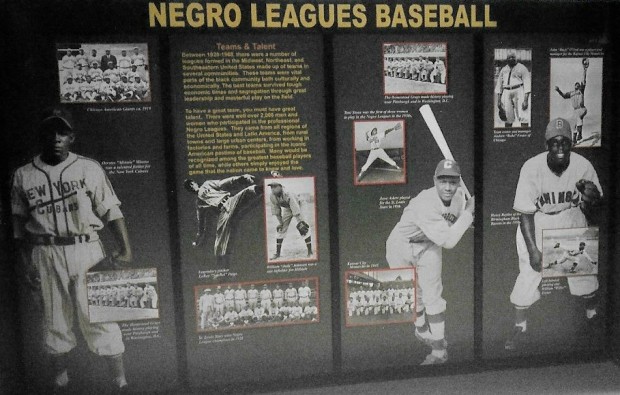

Black ballplayers formed teams and “barnstormed” around the country playing exhibition games against white competition. In 1920, Rube Foster founded the National Negro Baseball League so black players had an organized professional league in which to compete against one another. On a tour of the museum, we learned about the great Negro League teams — the Homestead Grays, Kansas City Monarchs, Pittsburgh Crawfords and New York Black Yankees — and the colorful players who played for them: “Turkey,” “Double Duty,” “Wild Bill,” “El Diablo,” “Bullet Joe,” and “Mule.”

The centerpiece of the museum is a ball field with life-sized bronze statues that appear to be playing a game. We were the only patrons at the museum that day, so at the end of the tour, we walked around and studied the “Field of Legends.” The Negro League stars on the field represented the best players of their era: Leroy “Satchel” Paige, pitcher, the brightest star of the Negro League. Josh Gibson, catcher, the “Black Babe Ruth” allegedly hit 80 home runs one season. Buck Leonard, first-base, “Sneaking a fastball by Buck was like sneaking sunrise by a rooster.” Pop Lloyd, second-base, known as the “Black Honus Wagner.” Ray Dandridge, third-base, he was called “Hooks” because he snagged baseballs like they had hooks in them. Judy Johnson, shortstop, a versatile infielder from Snow Hill, Md. Oscar Charleston, center-field, who Buck O’Neil said was “Willie Mays before Willie Mays.” Cool Papa Bell, left-field, “He was so fast he could turn out the light, get dressed and be under the covers before the room got dark.” Leon Day, right-field, also a great pitcher; played in Baltimore. Martin Dihijo, batter, the only player inducted into the baseball Hall of Fame in three countries. Buck O’Neil, manager, standing on the front steps of the dugout, he was a beloved good will ambassador for the game of baseball. Rube Foster, the founding father of the Negro League, was the last man honored with a statue.

Baseball’s proudest moment,and a watershed moment in American History happened in 1947 when Branch Rickey, the general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers, hand-picked Jackie Robinson to break the color barrier in Major League Baseball. When the Dodgers recruited Jackie from the Kansas City Monarchs, he brought the exciting brand of Negro League baseball, built around speed and aggressive base running, to the major leagues. Jackie’s signing hastened the decline of the Negro League since all of the best black ballplayers were recruited to play on major league teams. By 1955, the Negro League was gone. Hank Aaron was the last big league ballplayer to play in the Negro League.

No less of an authority than Martin Luther King, Jr. said Jackie Robinson was the founder of the Civil Rights movement. The words written on Jackie Robinson’s tombstone speak volumes about the man and his legacy: ” A life has meaning only in its impact on other lives.”

Arthur Bryant’s World Famous BBQ Restaurant was a short walk from the museums, so we went there for lunch. We got cafeteria trays, waited in line and placed our orders at the counter. The server put on a show. “You are about to have some real barbecue, Bam! he exclaimed as shoveled large portions of tasty barbecued beef and pulled pork on our plates. We shared a pitcher of beer to wash it down.

When we left the restaurant, storm clouds had gathered, the sky looked ominous and a tornado watch was in effect. “Boys, I would like to say we’re not in Kansas anymore, but we are,” I joked nervously. We drove through heavy traffic on Interstate 70 to Kauffman Stadium in the Harry S. Truman Sports Complex located in suburban Kansas City for the Friday night game between the Baltimore Orioles and Kansas City Royals.